Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga is seeking feedback on its draft conservation plan for the Mangungu Mission House at Horeke.

July 13

MEDIA RELEASE

Have your say on Mangungu Mission….

People can now have their say on the future care of one of Northland’s most important historic places.

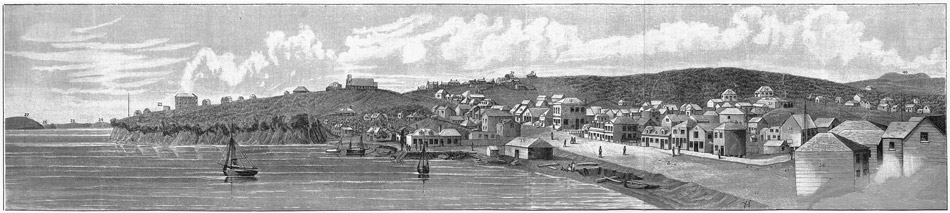

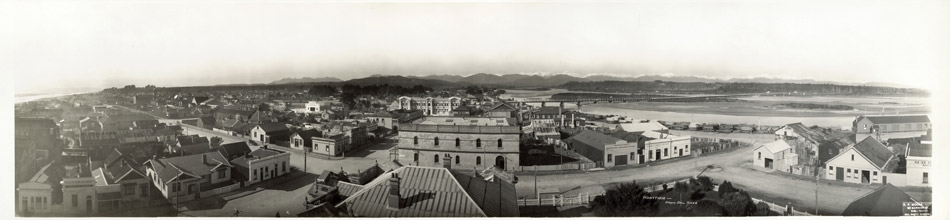

A conservation plan for Mangungu Mission – the site of the Wesleyan Mission that was established in 1828, and which later became the site of the largest signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi and the place where honey bees were first introduced into New Zealand – is now available for people to give feedback.

The process will be overseen by Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga which manages the Category 1 historic place, and will include public meetings at Kohukohu, Rawene and Horeke.

“The purpose of the plan is to provide guidance on the care and management of the Mission House, and to protect and conserve its cultural heritage significance for future generations,” says Heritage New Zealand’s Property Lead Hokianga Properties, Alex Bell.

“Thanks to the success of the new cycleway, Mangungu Mission is no longer the quiet backwater it may have been five years ago. It’s increasingly becoming a tourism destination in its own right, and is also one of Northland’s Landmarks Whenua Tohunga.

“It’s important that we care for and maintain this very important building well, and that means getting the conservation plan right – because ultimately the plan will guide us on things like maintenance and restoration as well as interpretation, and even promotion of Mangungu Mission.”

Hokianga iwi and hapu have a close connection to Mangungu Mission, and the original signing of the Treaty in the Hokianga on February 12 1840 is commemorated by the community every year. The Mangungu signing of 1840 drew about 3000 people on the day, with about 70 rangatira signing Te Tiriti after a period of rigorous debate.

“Many people feel a strong connection to Mangungu for its Tiriti and mission history, and we would like to hear from anybody who has an interest in this place to find out their stories and associations, and why the place is important to them,” says Alex.

“The information we collect during this process will help inform the conservation plan.”

The primary focus of the plan is the mission house itself, which has had a fascinating history. Originally constructed in 1839, it is one of this country’s oldest buildings.

“Amazingly, the house was shipped down to Onehunga in Auckland where it was used as a parsonage and home. It was then trucked back up to Mangungu where it was reassembled on the original site of the mission in 1972,” says Alex.

“Even though it has been shifted, the house has important heritage fabric and values, reflecting the story of early contact between Maori and Europeans, the introduction of Christianity and, of course, Te Tiriti.”

Once consultation has been completed, comments received will be evaluated and written into the plan as appropriate. The plan will then be presented to the Heritage New Zealand Board and Maori Heritage Council for approval prior to being adopted and implemented.

As well as the public meetings, people are also able to lodge written comments about the plan to be received by Heritage New Zealand no later than (4.00pm) August 24, 2018.

“Everyone who has an interest in Mangungu Mission is invited to the meetings or to make a submission,” says Alex.

“Mangungu is important to a lot of people, and we want to ensure the Conservation Plan is the best it can be.”

The draft conservation plan has been publicly notified and is available on the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga website http://www.heritage.org.nz/protecting-heritage/consulting-on

A reference copy will be also available at the meetings as well as in the Northland Area office (62 Kerikeri Road, Kerikeri).

Please send your written comments to the following address by 4pm on Friday 24 August 2018.

Calum Maclean

Policy Advisor Kaitohutohu Kaupapa Here

Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga

PO Box 2629

Wellington 6140.

email: cmaclean@heritage.org.nz.

"Practical changes to unreinforced masonry securing initiative"

"Practical changes to unreinforced masonry securing initiative"