July 30

MEDIA RELEASE

Te Pakanga o Ōhaeawai listed as a Wahi Tapu

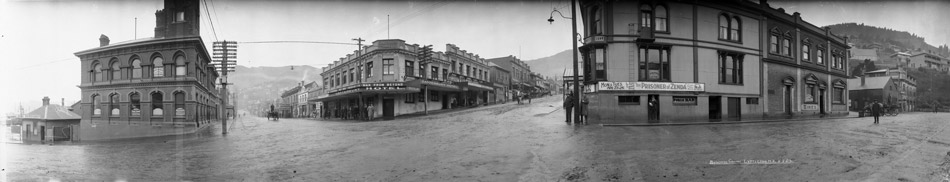

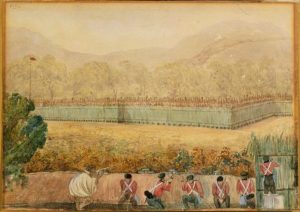

The pā at Ōhaeawai today. The pā also incorporates the urupā, in the middle of which stands Te Whare Karakia o Mikaere [St Michael’s Church].

Te Pakanga o Ohaeawai has been added to the New Zealand Heritage List as a Wāhi Tapu Area by Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga.

Under the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act, a Wāhi Tapu is defined as a place sacred to Maori in the traditional, spiritual, religious, ritual or mythological sense.

“Te Pakanga o Ōhaeawai is a hillside near Ngāwhā where a faction of Ngāpuhi under Te Ruki [The Duke] Kawiti successfully defended the pā of Pene Taui, of Ngāti Rangi, against British forces led by Lieutenant Colonel Despard in June-July 1845,” says Heritage New Zealand’s Northern Pouārahi, Atareiria Heihei.

“The fortifications were ground-breaking in every way, and became one of the prototypes for gunfighter warfare in later engagements.”

“The pā at Ōhaeawai is tapu to Ngāti Rangi as a place of battle and bloodshed. It also incorporates the urupā, in the middle of which stands Te Whare Karakia o Mikaere [St Michael’s Church].”

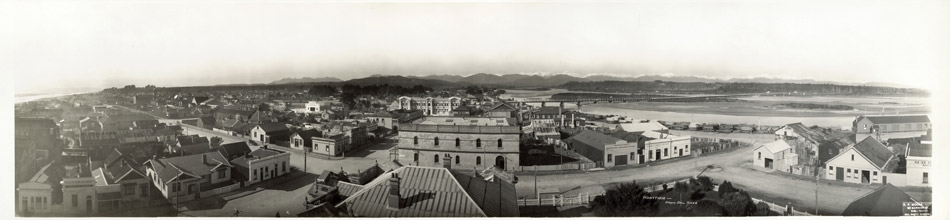

It is also the original site for the placename “Ōhaeawai”, although the name was exported to the nascent township 4km down the road in the 1870s.

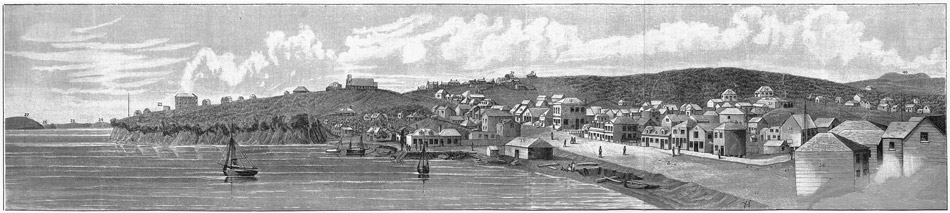

The peaceful vista of today is very different from the scene of carnage that occurred on July 1, 1845 during the third major engagement of the Northern Wars.

“On June 25 about 600 troops from the 58thand 99thRegiments, the Royal Marines and militia – as well as approximately 300 warriors of Tāmati Wāka Nene – besieged about 100 men in Pene Taui’s pā at Ōhaeawai,” says Atareiria.

“Prior to the attack, Pene Taui had insisted that the battle take place at his pā, which Kawiti had agreed to. Kawiti subsequently fortified the pā for this purpose.”

Kawiti and Taui did an exceptional job. The pā had two palisades – including a strong inner fence made of puriri logs set almost two metres into the ground with five metres of log standing above ground.

A curtain of flax matting hung on the exterior of the pā quenching musket ball fire, concealing the interior from the British and robbing them of such basic information as to whether or not their shelling was effective.

In addition, a trench located between the two palisades encircling the pā, provided protection for warriors reloading their muskets, who were then able to step up onto platforms that elevated them to ground level. From here they were able to fire their muskets almost completely concealed from the enemy.

If that wasn’t enough, some trenches extended beyond the shape of the pā to form bastions from which fighters could then shoot at attackers side-on as they attacked the pā. The coup de grace, however, was a series of rua [pits] that were underground compartments roofed with beams and timber – possibly the first example of an anti-artillery bunker.

The rua stood the defenders in good stead.

“The British established a four-gun battery on the nearby hill of Puketapu, and opened fire on June 25, continuing until it was dark,” says Atareiria.

“By the end of the day, however, they had done very little damage. The bombardment was to continue, equally ineffectually, for a further two days.”

Despite the bombardment – and the fact that they were outnumbered almost 10 to one – the defenders weren’t exactly throwing in the towel.

“On July 1 a raiding party from the pā successfully overpowered Tāmati Wāka Nene’s camp and took the Union Jack that had been flying there,” says Atareiria.

“The Union Jack was then flown within the defenders’ pā in full view of the British – upside down and at half mast below a Kākahu (Māori cloak). Despard was apoplectic with rage at the insult.”

Goaded into action, he ordered the storming of the pā. Although Despard’s offices and allies warned against attacking the heavily defended pā – and Wāka Nene, who had since recaptured his territory from the defenders, refused to participate in the attack – Despard would not be dissuaded.

“The disastrous assault went ahead,” says Atareiria.

“The solid palisades of the inner fence had withstood the artillery attack and remained intact, preventing the British from entering the pā. Meanwhile, the firing trenches proved devastatingly effective against the attackers. Within seven minutes of the attack beginning, over 47 of the attackers lay dead with about 70 more injured. The attack was an unmitigated disaster.”

Although more ammunition was brought in, and the British continued shelling for a few more days, the result had been a foregone conclusion. By 8 July, the pā was found to have been abandoned and the defenders had disappeared into the night.

“Although he tried to put a positive spin on the result, Despard had achieved nothing at enormous cost,” says Atareiria.

“He was to experience similar frustration at Ruapekapeka, where he would be confronted once again by an almost impregnable pā.”

Today, remnants of Pene Taui’s pā can still be seen in some of the undulations in the ground, though the area is predominantly an urupā with Te Whare Karakia o Mikaere at its heart.

“In 1871, Heta Te Haara, who had succeeded Pene Taui as the local rangatira after his death, wrote to the government for permission to remove the remains of the troops from the original burial site to where they currently lie inside the St Michael’s churchyard,” says Atareiria.

“On July 1 1872 – 27 years to the day of the battle itself – the troops were honoured by Māori in a service that was attended by a Government official representing the Under Secretary of the then Native Department, who reported on ‘the present good feeling, singleness of purpose, and perfect unanimity which very apparently existed between the Ngapuhi and their Pakeha neighbours’.”

The grandson of Heta Te Haara, kaumātua Ben Te Haara, remembers his grandfather talking about the battleground. His recollections were a vital part of the research as he was able to point out many features from information passed down to him – including the location of a line of pūriri trees that the British used to range their guns.

“The information that Ben Te Haara and other kaumātua provided has been invaluable in informing our Wāhi Tapu listing,” says Atareiria.

“The listing formally identifies the tapu nature of this place to Ngāti Rangi, while also highlighting the importance of this place to all New Zealanders.”

Box Story:

A masterpiece of military engineering

One of the observers of the battle of Ōhaeawai was missionary Henry Williams. His wife, Marianne Williams, commented on the ingenuity of the construction of the war pā in one of her writings:

“It is quite astonishing how they seem to defy the British in their fortifications. They have double fences, ditches, and loop holes, their houses sunk underground; and as the great guns of the British are fired through their pa with so little loss to the rebels, it is supposed that they have large holes, in which they secure themselves. The fence around the pa is covered between every paling with loose bunches of flax, against which the bullets fall and drop; in the night they repair every hole made by the guns.”

Comments are closed.