Jacinda Ardern MP has generously provided us with a copy of the Address she gave to the Historic Places Aotearoa.

We note that :

"I will leave with you a few of these thoughts in writing. Please do feel free to take the time to think about them, and any other ideas you have in this space. I would welcome your thoughts."

The Address is as follows:

I want to start by acknowledging the manawhenua of this land. I also want to acknowledge James, and all of the executive of Historic places. You do incredible work.

Long before I took on the portfolio of heritage spokesperson, I had a love of heritage. I have often wondered where it started. Was it when I first read a book about Antarctic exploration, a particular passion of mine that probably seems normal now, but as a 14 year old girl growing up in Morrinsville who had never seen snow, it was slightly less normal.

The idea though, that huts that once housed these explorers still stood, and in many cases, had been restored and preserved on the ice as a rarely seen capsule of history was absolutely fascinating to me. But if I’m honest, my amateur appreciation started well before that.

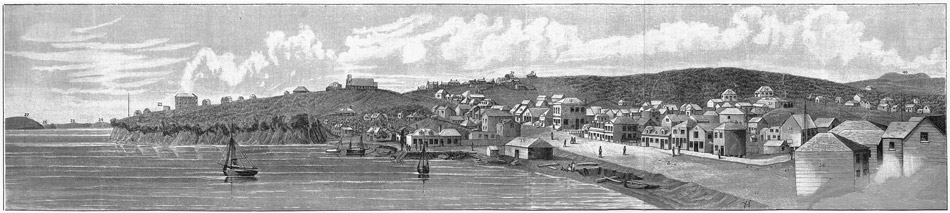

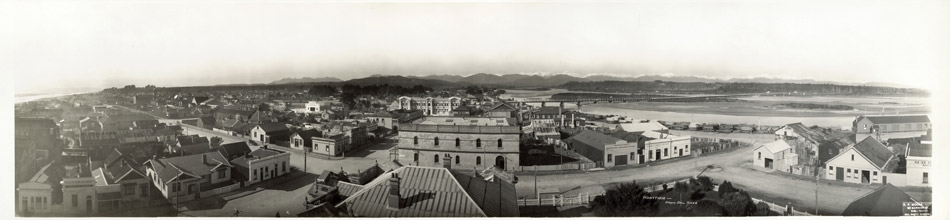

It started in Te Aroha. If I were to name one place that is an anchor for me, it is this small town nestled between the Hauraki plains and the rural Waikato. Both of my parents were born under this mountain. My mother’s family farmed along the Waihou river.

My father’s family were drain diggers. As a child, most of my Sunday’s were spent in Te Aroha visiting my grandparents. My nana and grandad had a home on the edge of the historic domain, only 100 metres or so from the old geyser and colonial bath houses that people would visit to renew their health long before my family arrived.

My grandparents’ home was old. Really old. For a long time there was no inside toilet, and I remember being terrified of the spider riddled outhouse that sat next to the outside room with the copper that my nana did the washing in.

She would make sure that when we visited, she had the coal range roaring to not just heat the water, but to put a roast on. I can still remember when, finally, an electric oven was installed in my nana’s kitchen. She even used it…occasionally.

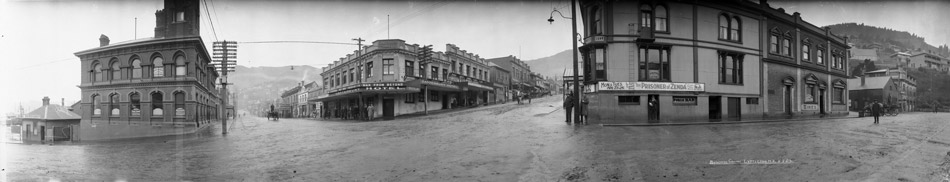

We would fill our visits with games in the domain, or on the steep streets that rolled down from Mt Te Aroha. Horrific flooding in that tiny town in the 80s meant that huge guttering, the likes of which I have never seen anywhere else, were installed down the streets that drained away from the mountain. My sister and I would use them for leaf races, starting at the top, and flowing all the way down to the historic old post office.

I always remember loving that post office. It remains the first heritage building I ever remember noticing as a child. It had what, to a child’s mind, looked like a royal seal at the top of it. I thought it was beautiful, the kind of thing the queen would visit, if she ever came to Te Aroha.

But it was more than that. That building was part of my mum and dad’s story. My Aunty used to work there as a telephone operator, probably listening to all of the calls. My mother worked their too, as a clerk. If you believe my father’s version of events, she would spy on my dad from the window on the top floor. I love that building. It’s not only beautiful, and a part of what makes that historic town, it is part of my story. And my families story.

Nothing that I have described is especially unique or special. I know that all of you, by virtue of the work you do, will have some personal and almost emotional draw to the buildings and places you work to protect – for the precise reason that they are not just buildings and places, they are memories and taonga.

I wanted to start by acknowledging those special relationships. But, having a feeling or sense of connection to these places, as we all know, is not enough.

We have to back it up, ensure that our protections are robust, that our advocacy is able to be meaningful, and that we achieve the outcomes that the public expects.

In my short time in the Arts, Culture and Heritage portfolio, there have been too many examples where that has not been the case.

Let me share a few issues that I have seen emerge over the years, that will not feel new to any of you.

The Christchurch earthquake was devastating in it’s enormity. There was so little in that situation that could be controlled, but how we dealt with heritage was one of them.

I wasn’t there, so I will never fully understand the enormity of it, and the justifiable fear that still exists today. But the ramifications from a heritage perspective, have obviously been huge. There was the immediate effect, which was to start pulling down buildings that were deemed to be a risk. That is utterly understandable. But some of the fear was squarely placed at the feet of historic buildings, in an environment where it was extremely hard to point out that they had in fact, not taken lives.

The Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Act of course allowed this demolition work to continue, giving broad sweeping powers which cut out the RMA process. Like I say, I don’t want to trivialise or diminish the situation that led to those powers, but in our minds by 2014, when 47% of the listed heritage buildings in Christchurch central city had already been demolished, it was more than time for those extraordinary powers to come to an end.

We called for the section 38 of the CERA act to be scrapped, for the quick fire demolitions to end, and more specifically we called for the public to have a voice on the future of the cathedral through a full RMA process.

The way in which the question of the cathedral has dragged, and has held up the rebuild of the central city has been hard to watch, not least for those who have made such a strong case for this historic buildings rebuild, and restoration. In our minds, there has been a case for stronger government intervention here.

But the ramifications of the earthquake have of course been felt even more broadly than that. In the wake of the quakes, the rest of the nation had revised insurance bills arrive, and for many in heritage buildings, they were crippling.

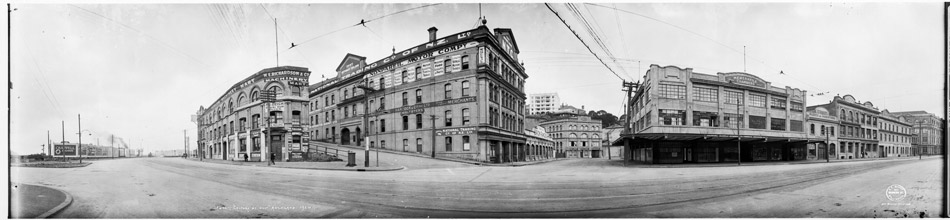

This really just compounds a second problem. The financial strain that often comes onto those who own heritage buildings, who are often unable to recoup their costs. Let’s take an example – the owner for instance of a heritage building in Fielding. Not only will they be facing hefty costs to ensure their building is up to scratch, this has often coincided with increases in insurance. If they run a business out of the building, there is rarely going to be any increase in profit as a result of upgrading a building, and if they rent it, there will be an expectation the building is safe without an unreasonable hike in their costs.

Add to that the fact that regional New Zealand has had it tough in some areas in recent years, and you have a recipe for vacating the property, allowing it to become run down, or both. I don’t say that to place blame on anyone, in my mind, the only thing we should be pointing the figure at is the great vacant hole where all of the ideas should be to fix this problem.

First, what assistance is there to help owners in these situations? As you know, there are options like the National Heritage Preservation Incentive Fund. But is this genuinely enough, and will it reach the shop owner in Fielding?

Relative to some of the schemes offshore, there is very little in place that acknowledges that there is a collective good to maintaining these buildings, and maybe it’s time we acknowledged that.

In our last manifesto, we talked about what we could do to remedy this situation. We set out that we wanted to investigate methods to ensure that heritage buildings in private ownership are not left in a state of demolition by neglect, triggered by for instance the expense of new earthquake proofing requirements. This could for instance include tax incentives to restore listed buildings. I would welcome your thoughts on this commitment, and what you think it should look life if we really want to make a difference in this space.

But we face another difficult challenge that has been exemplified in recent times – the issue of buildings that should be protected, that on paper have the highest protection we can offer, but have still been destroyed. You will know this issue all too well – there have been 26 listed buildings lost in the last 5 years. And probably the most recent tragedy that we will be adding to that list is Aniwaniwa

Many of you will already know about this architecturally designed visitors centre that sits in the bush near Lake Waikaremoana, and has done since 1976. It was a Category One Historic Place and one of national significance. It was designed by John Scott, a man who has been described by the Institute of Architects as not only a “pioneering Maori architect” but an “outstanding figure in twentieth Century New Zealand architecture.” John has passed, but he has left us some fine legacy buildings that we have a responsibility to protect.

The land this historic building sat on is held by Tuhoe; but the care and maintenance of the building, was up to the Department of Conservation. Concerns over the apparent ability of the building to withstand an earthquake meant the first floor was closed in 2007. By 2010 a report on weather tightness issues was interpreted to mean that the building needed to sit entirely empty and unused, and that is exactly what happened. Letters from around that time show that because DOC had no interest in going back into the building, they also had no interest in spending any money on it. Let’s face it, they were struggling to do their job with what budget they had, it was never going to be their priority. But it needed to be someone’s priority.

But it did appear at first that there might be hope. After all, the only person that ultimately we needed to convince to save the building was the Minister of Conservation, who helpfully happened to be the Minister for Arts Culture and Heritage.

And the building was already listed. There was not much more you could do to highlight it’s importance bar writing it in large red letters on the side.

But what happens when those who should be on your side, have an agenda. When those responsible for making a decision over it’s future, have a pre determined view, and when the local council has no requirement to take into account the heritage listing of a building, and instead condemn it?

The answer, sadly, is that we lose a taonga. I have not seen an example in recent times of just how shallow our heritage protections can be, than this case.

I want to acknowledge those in this room who fought so hard to save this building. We exchanged many phone calls, shared information, lobbied on every front we could. In desperation, I chased one minister out of the debating chamber, and passed notes in the house to others who seemed to be diligently avoiding me. Sadly, it came to naught.

But this experience has to count for something. That’s why I want to work with you collectively to come up with solutions that ensure Aniwaniwa never happens again.

The first question I would like to pose, is what happens to heritage listed buildings in crown ownership? Should all buildings in this category be managed by Heritage NZ? I have very little faith in the ability of DOC to preserve these buildings, and they aren’t resourced to either. Turnball house for instance is also in their care, and continues to sit empty. There will be others. Would such a change make any meaningful difference, or at least ensure improved maintenance of listed buildings?

Secondly, how do we ensure listed buildings are given due regard at a local level? I have seen a few ideas floated in this space, and if you indulge me for a moment, I would like to canvas a few with you.

Firstly, if you look at the interface of the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 2014 (HNZPTA) with the RMA, there is a gap in what councils must have regard to.

S74(1) of Heritage NZ act states as follows:

74 When local authorities must have particular regard to recommendations

(1) In respect of a historic area entered on the New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero, Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga may make recommendations to the local authorities that have jurisdiction in the area where the historic area is located as to the appropriate measures that those local authorities should take to assist in the conservation and protection of the historic area.

Under s65 historic areas and historic places are different things, so adding historic places to part one would strengthen the Act to a degree. But there are also plenty of caveats in there, and this amendment is probably the least we could do.

Another option is to make amendments to the RMA itself. Section 74 for instance states that

74 Matters to be considered by territorial authority

(2) In addition to the requirements of section 75(3) and (4), when preparing or

changing a district plan, a territorial authority shall have regard to—

(a) any—

(i) proposed regional policy statement; or

(ii) proposed regional plan of its region in regard to any matter of regional

significance or for which the regional council has primary

responsibility under Part 4; and

(b) any—

(i) management plans and strategies prepared under other Acts; and

(ii) [Repealed]

(iia) relevant entry on the New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero

required by the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 2014;

and…

It could be possible to strengthen this section by specifying category 1 historic places, but again, this would only require council to have regard to these buildings. Evidence to date suggests this might be too weak.

The third option relates to Section 75 of the RMA, which states

75 Contents of district plans

(1) A district plan must state—

(a) the objectives for the district; and

(b) the policies to implement the objectives; and

(c) the rules (if any) to implement the policies.

(2) A district plan may state—

(a) the significant resource management issues for the district; and

(b) the methods, other than rules, for implementing the policies for the district;

and

(c) the principal reasons for adopting the policies and methods; and

(d) the environmental results expected from the policies and methods; and

(e) the procedures for monitoring the efficiency and effectiveness of the

policies and methods; and

(f) the processes for dealing with issues that cross territorial authority boundaries;

and

(g) the information to be included with an application for a resource consent;

and

(h) any other information required for the purpose of the territorial authority’s

functions, powers, and duties under this Act.

(3) A district plan must give effect to—

(a) any national policy statement; and

(b) any New Zealand coastal policy statement; and

(c) any regional policy statement.

(4) A district plan must not be inconsistent with—

(a) a water conservation order; or

(b) a regional plan for any matter specified in section 30(1).

There are two options here. We could either amend this section to include a requirement that a district plan must give effect to any recommendation about a category 1 historic place

Or, we could opt for the nuclear option, and finally create a national policy statement on heritage.

This is something we have been thinking about for sometime, and in fact, its something we included in our last election manifesto. But I am genuinely keen to hear from you what you think will make the biggest difference.

After today, I will leave with you a few of these thoughts in writing. Please do feel free to take the time to think about them, and any other ideas you have in this space. I would welcome your thoughts.

Finally though, please let me finish with a word of thanks. For every lost historic place we have mourned, there will be one that your hard work and advocacy will have saved. I look forward to working with you to ensure that happens much more often.

Comments are closed.