Dr. Ian Lochhead has generously made available the submitted text for the article "Symbol of great innovation" published in The Press. Note: The text provided by Dr. Lochhead differs slightly from the resulting published article.

Dr. Ian Lochhead has generously made available the submitted text for the article "Symbol of great innovation" published in The Press. Note: The text provided by Dr. Lochhead differs slightly from the resulting published article.

The article is a response to Minister Brownlee's "Modern city needs new town hall" (Press Online).

Why we should value the Christchurch Town Hall

Minister Brownlee’s statement that the Christchurch Town Hall should be demolished (Press, 17 June 2013) comes as no surprise. The Minister had already expressed this view following the City Council’s unanimous decision late last year to fully strengthen and restore the complex. What is more surprising is the context in which his claim has been made. CERA has made it quite clear that the decision on the future of the Town Hall is to be the Council’s responsibility and the CCDU Blueprint for the central city also acknowledges that the final design for the proposed Arts Precinct is contingent upon whether the Town Hall is retained. If the building is as damaged as the Minister asserts, and if the geotechnical conditions are as problematic as he claims, why was the retention of the Town Hall even contemplated in the Blueprint? This is the plan for the city that the Minister himself has signed off, yet he seems ready to selectively ignore its implications and to pre-empt the Council’s legitimate decision-making process. It is also worth noting that public submissions on the Council’s 2012 Annual Plan overwhelmingly supported the full retention of the Town Hall.

The most curious aspect of the Minister’s Perspective article is his argument that because it has proven necessary to carry out extensive modifications to the Sydney Opera House, a building that is more or less contemporaneous with the Christchurch Town Hall, the Town Hall must itself be no longer fit for purpose in a 21st-century city. Such an argument rests on even more shaky ground than that on which the Minister alleges the Town Hall stands. It has long been recognised that the design of the Sydney Opera House was compromised even before the building was complete. Conflict between the architect, Jorn Utzon, and the New South Wales Government over uncontrolled cost escalation resulted in the architect’s resignation and refusal to ever return to Australia. Political interference in the design process resulted in the spaces of the two main halls being swapped, the opera theatre being squeezed into the space designed for the concert hall and the concert hall expanding into the more generous space intended for opera. As a result the pit in the opera theatre is too small to accommodate the full orchestra required for some productions, the stage has limited wing and fly space and seating capacity is too limited to meet demand as well as forcing prices higher than would be necessary in a larger-capacity hall. All these problems were there from day one and for the last forty years has seen an on-going struggle to make the opera house work effectively. These problems are acknowledged in the self-deprecating claim sometimes heard in Australia that the “Lucky Country” has the world’s finest opera house, the only trouble being that the exterior is in Sydney and the interior in Melbourne.

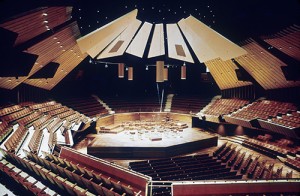

In comparison with the multitude of problems that beset the Sydney Opera House from the start, the commissioning, design and execution of the Christchurch Town Hall has always been considered exemplary. It was completed on time and on budget and for a fraction of the cost of the Sydney Opera House’s $120 million. What is more it was a paradigm-shifting building that changed the way in which concert halls around the world were designed from that time onwards. The New Zealand acoustic engineer responsible for the hall’s remarkable sound was Harold (now Sir Harold) Marshall and it was he who developed the theory of lateral sound reflection that was brilliantly put into practice in Christchurch. Sir Harold is convinced that the innovation he achieved in Christchurch, working closely with the architects, Warren and Mahoney, would never have been possible in Europe or America, where the inertia of received wisdom would have ruled out his radical and untried approach. Yet the design team’s willingness to innovate was brilliantly vindicated by the combined resonance and clarity of the hall’s sound. Rather than advocating the demolition of the Town Hall we should take pride in this unique, world-beating Kiwi success story. Far from being out of date for a modern city, the Christchurch Town Hall set the standard that cities around the globe have striven to emulate ever since.

Currently the eminent French architect, Jean Nouvel, in conjunction with Marshall Day Acoustics, is overseeing the completion of their design for the Philharmonie de Paris, a 2400-seat concert hall commissioned by the City of Paris and the French Ministry of Culture. (The budget for the Parisian hall is 200 million euros; Christchurch’s only slightly smaller hall was built for $4 million). We should be proud that the journey towards this new concert hall in one of the world’s great cultural capitals began in Christchurch. It would be a sad commentary on our national failure to recognise what is best in our own culture if we allowed such a significant building to be demolished. Australia has rightly celebrated the significance of the Sydney Opera House by nominating it for World Heritage status as a masterpiece of 20th-century architecture. Rather than advocating demolition of the Christchurch Town Hall, Minister Brownlee would be serving the interests of Christchurch’s recovery far better by advocating for its restoration and future nomination for World Heritage status, since the building’s international significance is surely equal to that of the Sydney Opera House. While the Sydney Opera House is a design of great engineering sophistication and sculptural presence, the Christchurch Town Hall redefined the very concept of the modern concert hall, something to be equally celebrated.

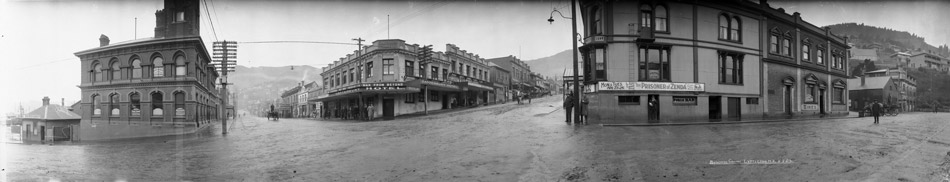

In an previous Perspective article in march 2012 (www.stuff.co.nz/thepress/ opinion/perspective/6602198/Let-our-public-living-room-live-again) I explored the many other reasons why we should restore our Town Hall and all these reasons still hold good. It is, as I argued then, our civic living room, the space in which we have come together as a community for many different occasions: to enjoy performances of many kinds by professional and amateur musicians alike; to recognise educational achievement and debate important issues; to celebrate and sometimes to mourn; to welcome new citizens into our community. It is one of the key buildings that help to define who we are. If Minister Brownlee succeeds in his desire to demolish the Town Hall he will have erased part of our communal memory and obliterated part of our collective identity. We must not allow this to happen.

Dr Ian Lochhead

Associate Professor of Art History

University of Canterbury

Comments are closed.